Fernand Roda

by Ina Helweg-Nottrot (2006) · translated by A. Moussa (2019)

The days in which the avant-garde – a rather anachronistic concept nowadays – belittled or treated nature with contempt, have long since gone.

The theme of nature has regained a firm place within art. One of the artists whose paintings examine this theme in all its different facets is the painter Fernand Roda, born in Luxembourg in 1951.

Just as “natura non facit saltus”, Roda develops his “pictures of nature” with determination, in a continuous, progressive and by no means erratic fashion. His paintings seem to be moving with rhythm, repeating seemingly naturalistic content or composing abstract forms into compelling visual motifs that captivate the observer. Art which embodies authenticity, in which one cycle follows the next. His works are exciting, since they do not traverse beaten paths, nor do they contain platitudes in ever new packaging; instead the works in their entirety reveal a process, a growing, a moving forward in the profession of painting. At the same time, as the painter emphasizes in 1995, “the conceptual, the abstract, and the visible elements are equivalent, they issue the irrevocable statements in my paintings in conjunction with each other.”

Roda’s works can be found in numerous private collections abroad and in Luxembourg, in the collection of the Musée National d’Histoire et d’Art, in numerous public buildings, as well as in the collections of the Bayerische Landesbank (Bavarian State Bank), Fotis Bank (BNP Paribas), BCEE (Banque et Caisse d’Épargne de l’État), Deutsche Bank and, of course, in the Dexia BIL (Banque Internationale à Luxembourg).

First steps in the art capital of Düsseldorf

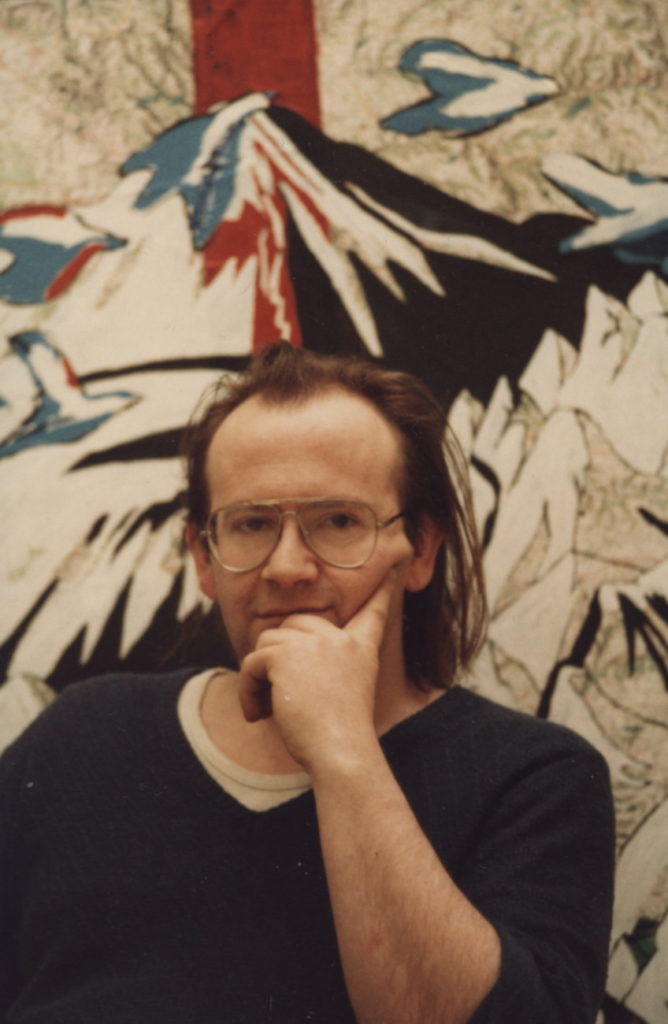

Ten years before Fernand Roda moved from Luxembourg to Düsseldorf in 1971, Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) had taken up a professorship in sculpture at the Staatliche Kunsthochschule Düsseldorf. During those years, the city by the Rhine was famous for its vibrant, bustling cultural scene, luring art lovers and students such as Fernand Roda to Düsseldorf. To the young student, Beuys was “[…] in his role as professor, the very opposite of what he was to me as a performance artist. He was a strict, classical teacher.” Contrary to what one might assume, Beuys taught traditional topics and techniques, such as painting, sculpture and sketching. This included drawing an object over and over again until it was mastered. Roda summarizes his experiences with Beuys as follows: “I was very fortunate to be challenged by Beuys. As a professor he was always present and very strict – he himself studied under Mataré – and tried to pass on his knowledge to the students. He had high demands in terms of basic prerequisites, and was known to have these high demands, especially when it came to drawing. After the second semester, he tried to show me where my strength lay and thus enabled me to work independently.”

Nevertheless, Roda, who studied alongside Lothar Baumgarten, Jörg Immendorf, Blinky Palermo and Katharina Sieverding – to name but a few of his well-known peers – categorically rejected the type of “altar obeisance” that was commonly paid to the idolised teaching personage. Accordingly, he took purposeful steps to draw a line under this stage of his education, to expand his own scope, and to not become his teacher’s extended arm; thus between 1972 and 1974 he created an impressive large-scale work: “Ende einer Avantgarde” (An Avant-Garde’s End). Even then, at the young age of 21, Fernand Roda had a keen sense that the art of the sixties and seventies – pop, minimal and zero – was outdated, that it was time to tread new paths. In 1981, the Düsseldorfer Hefte noted: “All of his subjects resided in the Grafenberger Allee, in houses that have since been demolished. Here, in these dilapidated rooms and apartments, young students such as Horst Gläsker, Milan Kunc, Jan Kolata and Anno Leven broke new ground. Roda placed thirteen of his peers around a table, portraying them as a serious society with bow tie and shirt … He painted each of his colleagues in his own style. Roda saw himself as a refined gentleman, glasses and thinker’s brow, his face half red, half blue.”

It was with this very work that Roda submitted to apply for Beuys’ master class. Roda explains that he was accepted, “although the Beuys class was a sculpture class and did not lean towards painting at all. Beuys himself was highly enthusiastic about the painting.” For Roda’s further artistic development, the painting marks a kind of milestone, for within the sculptor class he could only study painting on the side. A rigorous reorientation followed: “This represented a break with sculpting for me. Since then, I mainly focus on painting. One could say, it was a type of conscious caesura, the end of a cycle.” These days, “Ende einer Avant-garde” is a contemporary document, part of the collection of the Düsseldorf Museum of Art.

In 1976, towards the end of his studies, he shot a feature film with several friends, writing the script and taking on the role of director: “Die Missabenteuer des Anarchisten A.F.W.” (The Misadventures of the Anarchist A.F.W.). For Roda, a “vicious satire”, a “swan song on debating under Beuys.” In this manner, he cut the final cord, going his own way, independent of his charismatic teacher. An interesting side note in this context is Istanbul, with two different exhibitions in 2000: One reflecting the artist Beuys and the other his students, among them Fernand Roda.

Looking back at the eighties …

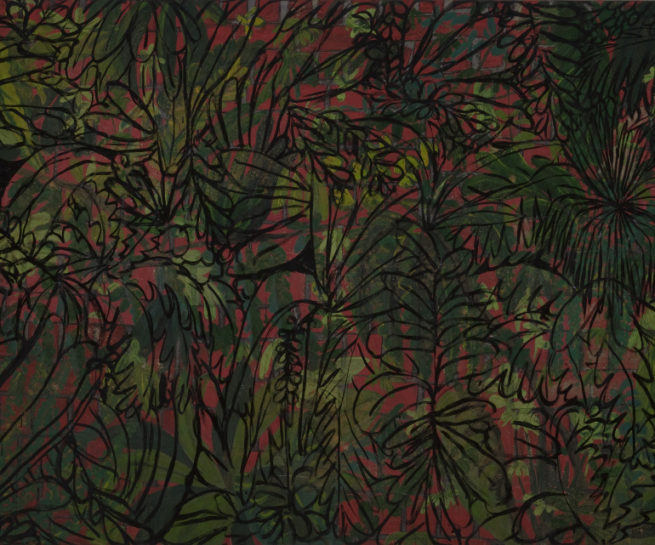

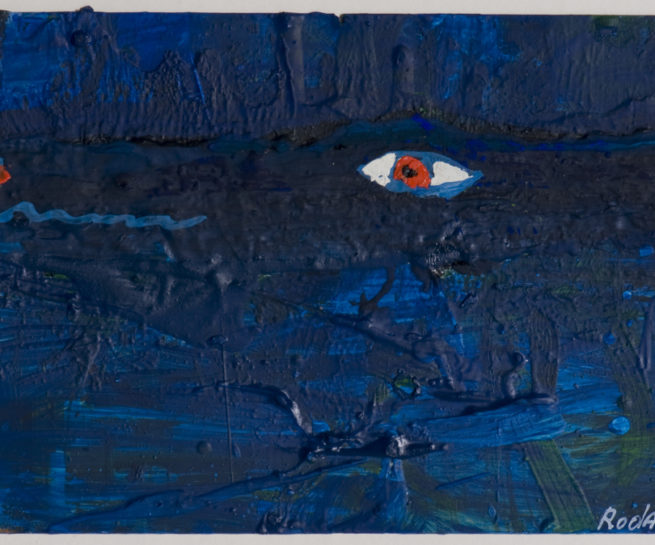

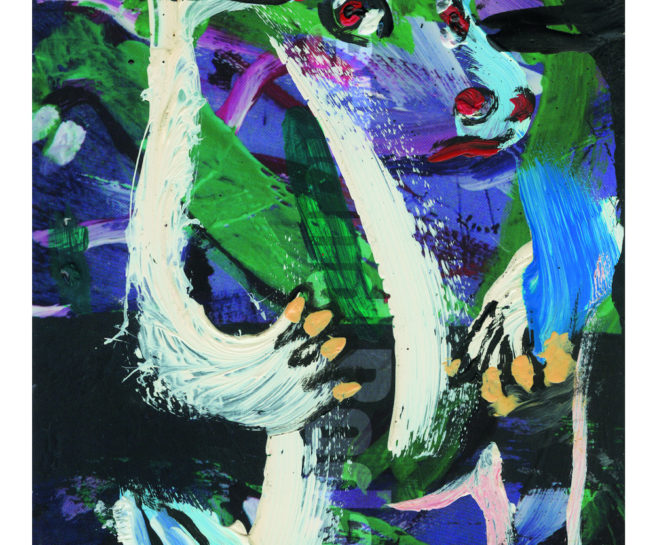

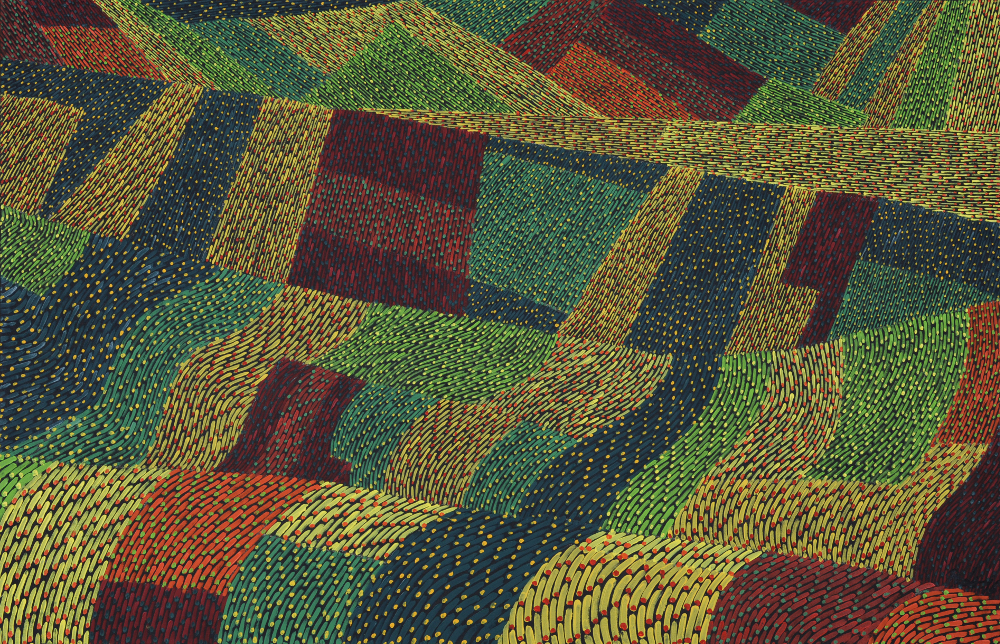

At this point we revisit some of his earlier paintings in order to gradually approach the currently exhibited works: First, the eighties with expressive-abstract works, featured at the 4th Triennial in Milan’s Palazzo della Triennale in 1980, and two years later “Ciel égyptien” (1981), presented during the 12th Biennale des Jeunes in Paris. An expressive, playful wickerwork characterizes works shown at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin (Academy of Arts Berlin) as part of the exhibition “Neue Malerei aus Deutschland” (New German Painting), such as “Taucher: Rotes Meer” (Diver: Red Sea) or “Nebelwald” (Cloud Forest). The latter, brimming with iconography and small ornaments embedded in a fantastical tropical forest, draw the viewer into a world of exotic visual inebriation with its lush plant worlds. Four years later, “Rezlop” follows and in 1987 Roda finishes “Kraft II” (Power II). Then Chaos – differently put, Order in Disorder, or Disorder in Order – in the 1988/1989 series shown at the XXe Biennale in São Paulo in 1989: “Tempus Praeteritum”, “Tempus Praesens” and “Tempus Futurum”. Fernand Roda explains: “Les 3 Tempus constituent une caricature du monde, de la relation à la fois amicale est hostile de l’homme avec son monde. La situation actuelle vue par un artiste du XXe siècle.” Roda is wrongly labeled to be part of the “Neuen Wilden” (New Wild) due to the excessive riot of colours in his earlier works. His thoughtful painting style runs counter to this, however, as does the lengthy working process that characterize his works to this day.

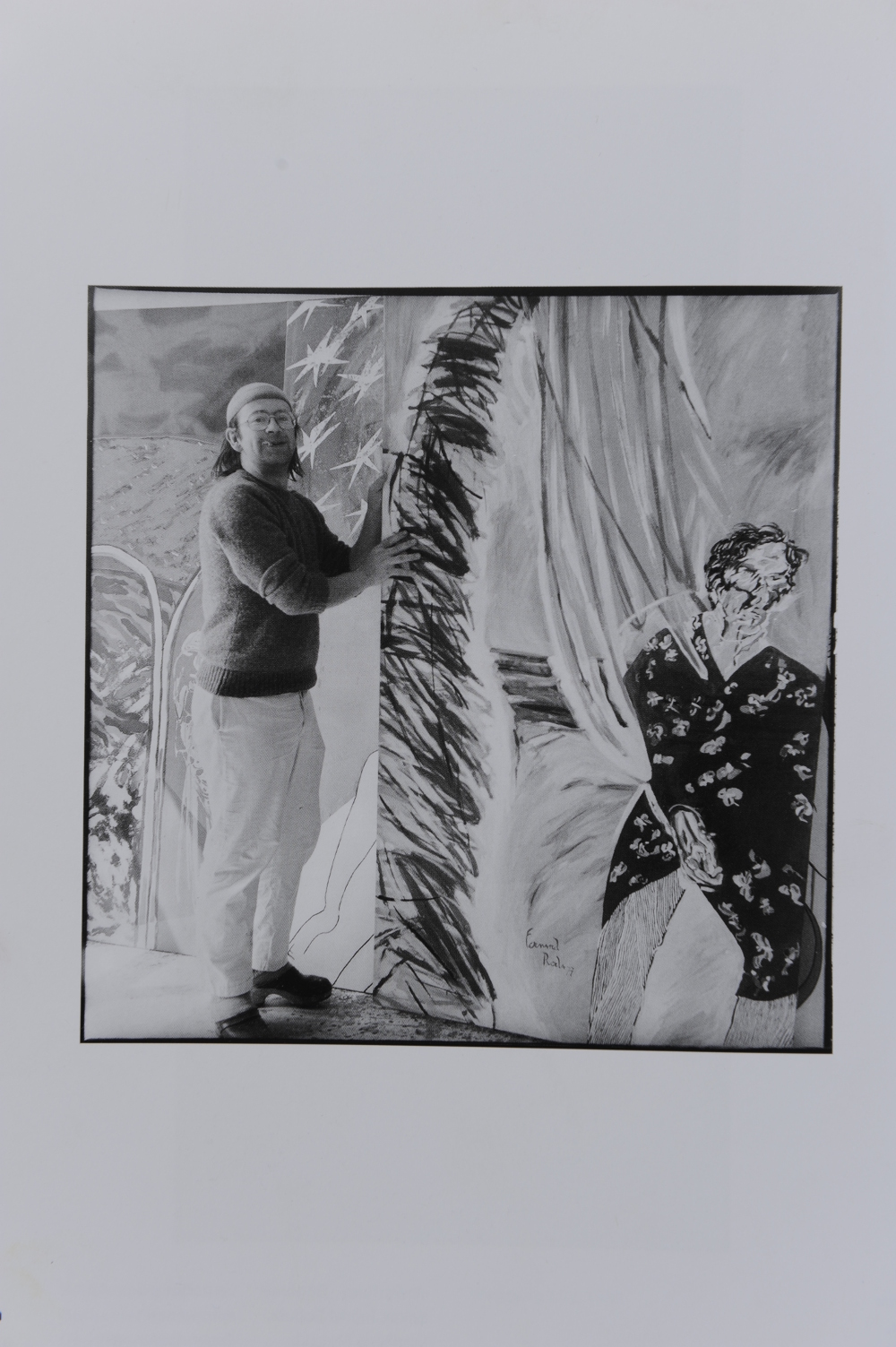

The “subway story” also dates back to the eighties. In a secret selection procedure, the museum directors of the city of Düsseldorf and several municipal representatives selected eight young artists living in Düsseldorf who were to help shape the Düsseldorf subway with public art projects. One of the chosen ones was Fernand Roda, who recalls: “When I returned from my vacation in the summer of 1987, people on the street approached me and told me that I was going to make a painting for the subway. All the newspapers mentioned it and I found out about it on the street.” In 1987/1989 Roda created his work for the subway station “Heinrich-Heine-Allee”, characterized by its impressive size of 4m x 3.6m. The composition is based on the painting “Entgleisung III” (Derailment III), the content of which is marked by tremendous turmoil: Three tunnel openings in the upper half of the picture discharge previously well-ordered railway tracks, turning into elevated track beams flying around chaotically and thus “derailing”. Lake and mountain range in the background are difficult to spot. They merely serve as enclosure to the theme, which, looking at the context in which it was created, strikes a rather allusive note.

… and the nineties

The beginning of the nineties was heralded by an important award. During the national holiday in 1991, Roda was awarded the title “Chevalier de l’ordre de Mérite du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg”.

The explanatory memorandum read as follows:

„Monieur Roda est le peintre luxembourgeois le plus connu en allemagne où il est actif depuis 1977, son rayonnement international ne cesse de croître, il est dans l’intérêt d’une politique culturelle aussi déterminée que celle que l’actuel gouvernement poursuit, de reconnaître le mérites de nos artistes importants à l’étranger et de consolider leur attaches avec notre pays en leur accordant une décoration luxembourgeoise.“

The early nineties feature works dealing with the earth as a geological site, such as “Untersuchung der Erdbasis I-IV” (Examining the Base of Earth I-IV) from 1990, supervening studies on the matter of colour due to the plasticity of its surface, bringing forth phenomena related to geomorphology such as stratification and packing. This is followed by the “Maschinenwelten” (Machine Worlds), shown in 1997 at the Schlassgoart Gallery. Although these works are influenced by functionalist aspects, the painter does not leaves nature behind here; rather he continues exploring it on a different level, engaged in the concept of technology resulting from it.

Looking back on the more than twenty years of work, one is captivated both by the continuity of the themes and, at the same time, the artist’s radical progress in his persevering confrontation with painterly implementation. It also becomes clear that this is an oeuvre that attaches no importance to the pigeon-holing of whether it is figurative art or not, concrete or abstract. As an artist, Roda – reflecting on this in a speech he gave at the opening of an exhibition in 1993 – strives to “preserve a different world for himself”, although nature, natural landscapes in art, are “of a different nature”. And: “This different nature, the nature in art, has to be discovered.” The extensive exhibition in the newly opened Gallery l’Indépendance enables visitors to trace this enigmatic characteristic of art.

Still Düsseldorf

Even today, after 34 years of diaspora, the artist is still convinced of his base in Düsseldorf. During a conversation at the long wooden dining table – with “Himmel und Erde” (Sky and Earth) from 1990 imposing its undeniable dominance in the background -, he tells us that the “Düsseldorfer Malkastenclub” still exists. Artists of the Düsseldorf scene meet there once or twice a month in order to exchange ideas in a relaxed setting. The latest project of the Malkasten is the “Düsseltaler”, a currency designed by artists that corresponds to its respective Euro value. The first edition is already in print, Roda being involved in the second edition. Each “player” receives a certain amount of banknotes, which can be put into circulation in stores participating in the project. An art campaign merging with everyday life.

A further reason for Roda’s loyalty to his location must surely be the spacious pre-war apartment of his Düsseldorf domicile. Near the city centre of the metropolis on the Rhine, it is apartment, studio and warehouse in equal measure. The view from the floor-to-ceiling windows of the studio reveals the charm of its backyard atmosphere that has grown over decades in the lavishly designed urban building ensemble. Certainly, a great place to work!

Nevertheless, the Luxembourgian, who grew up in Bertrange, has not been completely uprooted. He talks of the first meeting of the “exiled Luxembourgers” in Luxembourg with great enthusiasm. These include doctors, scientists, winegrowers, engineers or journalists – to name just a few of the professions represented – who were portrayed by Raymond Reuter in 2003 in his voluminous illustrated book “100 Lëtzebuerger ronderëm d’Welt” (100 Luxembourgers Around the World) and who gather at regular intervals with good food and, of course, good wine in order to exchange experiences from “dobaussen”.

Working process

Roda’s field of research is is a well-defined canvas as a carrier of form, his working method is highly disciplined and controlled. One will be hard-pressed to encounter any form of swaggering or the like. Various layers of paint are deliberately placed on top of each other, translucent layers allowing the observer to sense the process of forming a finished painting. Sketches and studies in oil pastel or pencil form the preliminary stages of his paintings, not by going outside and fixating what is to be depicted, but rather exclusively in the studio. After all, according to an interview with Roda in 1995, his works show “an abstract thought with cycle and composition forming the painting’s result, despite their beginning in figurative matter.”

A painter first and foremost, Roda prefers to work with pigment and oil paint, their colour and form providing the painter’s experimental starting point. Clear and energetic colours convey a strong message grabbing the observer’s attention like a maelstrom. Twisted, condensed layers of colour determine the composition with their distorting effects. Although Roda works with a traditional medium, he adopts innovative approaches by filtering all of his visual impressions within a lengthy working process in order to realize “the concrete motifs, the individual object, as an element of interpretation,” as the artist notes in 1995 in the accompanying text to the Robert Schuman Prize.

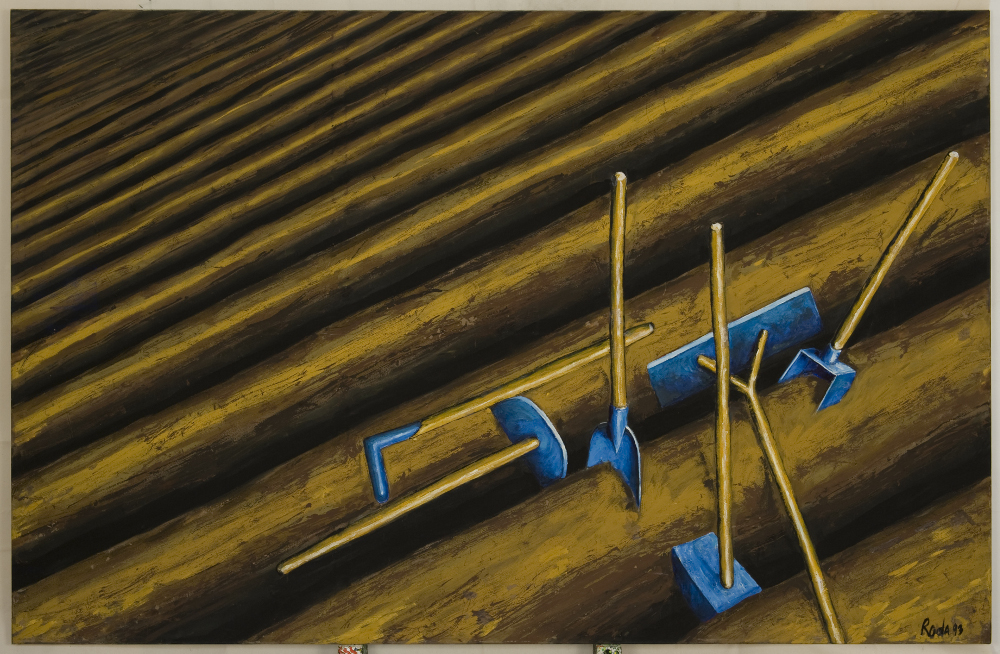

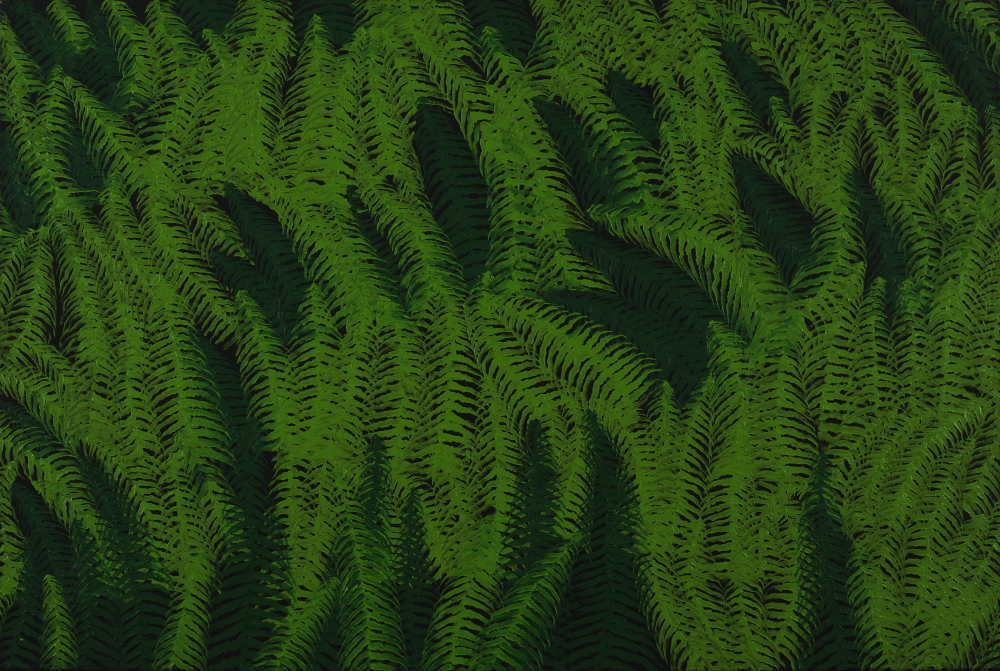

Imago

Whether it is topsoil, the uppermost layer of a field, with its clear plough furrows and voluminous plasticity produced by the black background painted subsequently, or birch trunks, or rich green ferns; the pictorial content appearing on Roda’s canvases seems to take on an almost realistic gestalt. And yet it is nothing more than an attempt to not distort the manifestation in any way, but rather to present with as much authenticity as possible.

For Roda, painting is essentially an act of self-questioning, with memory, fantasy and imagination providing the guidelines. At the same time, the process is linked to the theme of painting and serves the painter as an examination of painting itself.

Let us take a quick detour in order to illustrate two rather different approaches and working methods in “nature painting”. For this purpose I will draw on the Swiss painter Franz Gertsch and his style of photorealistic painting. Gertsch first had to photograph nature for works such as “Gräser III” (1997, 290×290), in order to paint them afterwards.

This is a completely different path than the one Roda chooses, which relies on the power of imagination: “The ability to doubt the sole reality of what is given and to contrast it with other realities – imagination – reveals the effectiveness of the Apollonian instinct”. It is not about attempting to come as close as possible to nature as a real gestalt or aiming to paint in order to emulate a model or template, but rather about painting as an act of self-assessment. Drawing upon nature on the one hand, and investigating the act of painting on the other hand. Art as a model of thought is a theme that Beuys also seized, Roda’s teacher once stating that: “The principles of art are the principles of spirit.” The works in the Kant exhibition reveal that the message of the paintings do not aim to merely mirror reality, but rather (and solely) reflect the subjective, artistic intentions of the artist. The process of realizing the painting is deliberately left visible, allowing one to rethink the actually visible world and resolving it during the process of thinking. This artistic strategy is made apparent in the painterly realization of works such as “Holzscheiben I, II, III and IV” (1994-1995).

Roda’s pictorial worlds are also his “intellectual worlds”, that “highly sensitive intuition of a desired different reality”. Roda explicitly refers to the philosophical excursions that accompany and theoretically underpin his works with exhibitions titles such as “Frei nach Kant” (Loosely Based on Kant) in 1996/1997.

We will embark on a short trip with Kant into the 18th century. Aesthetics became a discipline of its own when Immanuel Kant published his Critique of Judgment in 1790. Let us strap on our seven-league boots and briefly illuminate his theory: According to Kant, art is, first and foremost, something that we evaluate using our aesthetic judgement, ultimately making use of our personal taste. Art, however, only deserves to be called “beautiful”, if it seems like nature through emulation (not mimicry) and yet we are conscious of it as art. For Kant, the beauty of a work of art is not directed towards purpose: “Beauty is the form of the purposiveness of an object, so far as this is perceived in it without any representation of a purpose.“

“Nature is beautiful because it looks like Art; and Art can only be called beautiful if we are conscious of it as Art while yet it looks like Nature.” – Immanuel Kant

Thus, in the sense of philosophical truth, a work of art is useless, even though it exudes an effect as if it were useful for something. According to Kant, the “worth” of art lies in its “lack of purpose”. And according to Roda? “Since art is an expression created by the mind, it cannot be objectively evaluated as a science.”

“I’m not a landscape artist in the traditional sense,” Roda states during a 1993 speech at an exhibition at the Deutsche Bank, continuing: “The paintings are representations of nature shaped by my inner perspective, and yet they are undoubtedly reflections on the medium of painting; i.e. the primacy of art always takes precedence over possible representations of natural landscapes, as does the question what painting in particular can reveal to the observer in terms of interpretation.” Three years later, on the occasion of the already mentioned exhibition “Frei nach Kant”, Roda deepened his understanding of the subject in the accompanying catalogue: “[…] talking about nature also means talking about the painting process, resulting in a conflict between what one sees and what is real.”

The point is not to transfer reality onto a canvas. To put it into a nutshell, his intention is “not to paint what one perceives, but how one perceives.” The pictures concentrate on the fundamental, avoiding details of unessential side shows, and dismantle the “concrete objectivity of nature into manifestations” when they render what the painter has seen. Roda’s works are not decorative art that can be easily appreciated. Even if the content of the picture may, at first glance, suggest easy accessibility, his pictures actually demand that one occupies oneself with them by examining the pictorial structure.

A phenomenon that can be retraced if we look back to the year 1984. Roda created the painting “Japanische Garten” (Japanese Garden), which – two years later at an exhibition opening in Dortmund – prompted a critic to utter the following analysis: It “consists of four elementary layers, which could easily be separated from each other, and which could actually result in four individual paintings. Roda unravels nature into manifestations.” Frequently the works have a bizarre and subversive character to them – the observer comes to a standstill with the artist smirking in the background. The field and the garden tools in “Ackerfurchenbild mit Gartengeräten” collide two worlds that do not belong to each other and by no means correspond with each other. Nevertheless, the painter subtly merges them into a seemingly logical unity. Reality/illusion, abstract/concrete, sense/nonsense are combined in a playful manner as an ostensible connection.

On readability, or deciphering a cryptic code

Just like a book, a picture can be read and – depending on the genre – this is done on only a single level or – in the case of more demanding texts – on several levels at the same time. Roda indicates a readability of his works on two interconnected levels, the first the “semantic aspect of nature representation” and the second “the syntactic perspective of the working process”. The artist’s primary focus does not lie on the “literary aspect”, but rather on “concentrated painting”. He evokes illusions that, at first glance, suggest an “object”. Roda gathers his pictorial elements from the outdoors, choosing the birch trunks, the green-glowing ferns (sometimes like blazing flames, sometimes embedded in earthy brown), the water lilies, the autumn impressions, the rectangular hay bales and arranging them in serial bundles, detached from their initial context. The artist mercilessly pursues his statements by means of syntactic repetitions. Roda: “The methodology lies in playing with alternation and interchangeability, notwithstanding the apparent consolidation and inner pictorial stability.”

Repetition

In order to illustrate the aspect of repetition, we will take a short trip into the world of music, more precisely to Johann Sebastian Bach’s Goldberg Variations. Bach composed them between 1739 and 1741 for the harpsichordist J.G. Goldberg, who in turn provided the musical accompaniment for his employer Count Hermann Carl von Keyserlingk’s “nuits blanches”. It was “a piece that poses the question of what is art about it with a clarity seldom found. The piece presents a formal game, a game of forms. A simple theme in two to three voices paves the way – a simple melody, which is catchy but not particularly memorable. The theme is followed by 32 variations. Time and time again, the basic musical substance of the theme is illuminated and reproduced in a different way. The progression contained in the piece is intimately linked with repetition. To a certain extent, nothing new is added in the 50 minutes that the piece lasts, for example, in Glenn Gould’s famous interpretation.”

Why would such music spark interest? Perhaps we should let Kant reply, who stated that art is solely about “insight”. “It is therefore characteristic of art that it presents forms alongside which we can experience our insights. In dealing with art we do not learn anything concrete about the world in which we live and which we arrange for ourselves. We do not learn anything about what we understand about the world and how we understand ourselves in it. Rather, art conveys us experiences that it is actually possible for us to recognize and understand in the world in the first place”. And it is in this context that the Goldberg Variations – formal entities that help us to gain such experiences – belong.

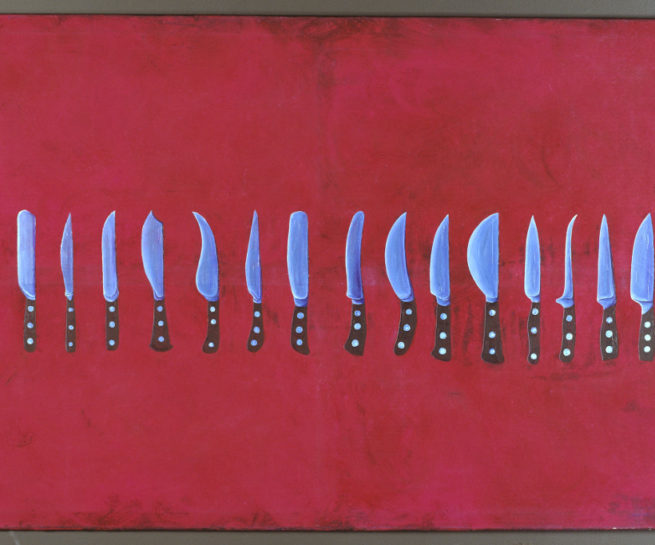

With this, we come full circle back to Roda. He stacks or strings together potatoes, tomatoes, wooden discs or bales of fabric in a seemingly banal fashion. “What for?”, the observer may ask. The pictorial element of the potato – that solanaceous plant accompanying our day-to-day life at the cooking stove – comes along in an endless longitudinal loop; playfully on the one hand, yet containing the audible echo of an ironic undertone in its pictorial manifestations on the other hand. Perhaps the artist is amused by our desire for unambiguousness, for aesthetics that can be appreciated on the fly, as it were a side dish?

Triptych

“The value of art lies in making comprehensible to us particular aspects of the world in which we live and of ourselves.” – Georg W. Betram

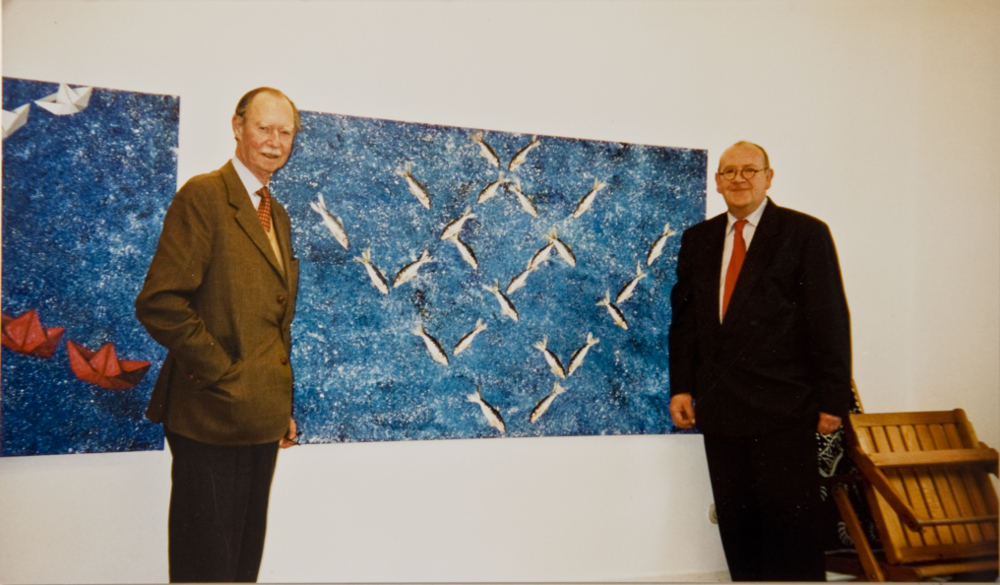

The new gallery building of the Dexia BIL allows the visitor to experience a downright visual frenzy. Its spatial conditions enable movement in the midst of huge formats and the possibility to enjoy a veritable “Roda wide-angle”. This is made possible through two adjoining booths with two correlating thematic areas – the diversity of agricultural fields, and meadows in their various manifestations.

“Die Macht des Alters” (The Power of Age), a group exhibition that could be seen in Berlin in the German Historical Museum as well as in the Kunstmuseum Bonn. During the group exhibition, curator Bazon Brock presented two of the large-format works that now turn up in a new constellation: “Zeit-Raum (Heute)” (1997-1998, 200×340), a potato field with an endless sequence of potatoes, and “Zeit-Raum (Morgen)” (1997-1998, 200×280), an endless sequence of germinating potatoes. Roda adds the “Ackerfurchen” (created during the same time period) to the above works in the Dexia BIL exhibition, creating an intensive visual experience, further bolstering its distinctive charm through its placement in a separate booth. The back wall of this booth opens to another area, setting the stage for another interconnected panel painting. In the centre, one finds the “Fallobstwiese” (1995, 340×200), bordered by “Apfelbild” (2004, 220×210) on the right hand side, and the lawn with its scattered plums of “Pflaumen” (2004, 220×210) on the left hand side.

Playing with perspective, or the art of false perspectives

We will take another quick detour in order to understand one of the more recent works from the year 2004 and the interesting phenomena it displays when it comes to perspective (perspicere = to see through). Perspective refers to the representation of three-dimensional space (length-width-depth) on two-dimensional painting surfaces. In the early 15th century, Italian humanists emphasized the importance of perspective in art, especially in order to shield themselves against the disdain of Plato. The depiction of size and space is entitled to a certain degree of relativity, but is calculability is nevertheless emphasized, covering it with the cloak of science and according painting a safe haven within the liberal arts.

Ernst Gombrich is clearly amused in light of the assumption that perspective is nothing more than an informal agreement or that it hardly portrays the world as it “really” looks like. He explains: “One must stress over and over again that perspective strives for an equation: The image should look like the depicted object and the depicted object should look like the image.”

Looking back in art history, we naturally come across a grandmaster, Leonardo da Vinci, who distinguishes three different types of perspective: “The nature of perspective is threefold. The first aspect determines the causes of things moving away appearing to be smaller. The second aspect contains the knowledge as to why colours change when they move away from one’s eye. The third and last aspect covers explanations as to why the further away things are, the less accurate their contours are to be depicted. These are respectively denominated linear perspective, colour perspective and perspective ‘di spedizione’.”

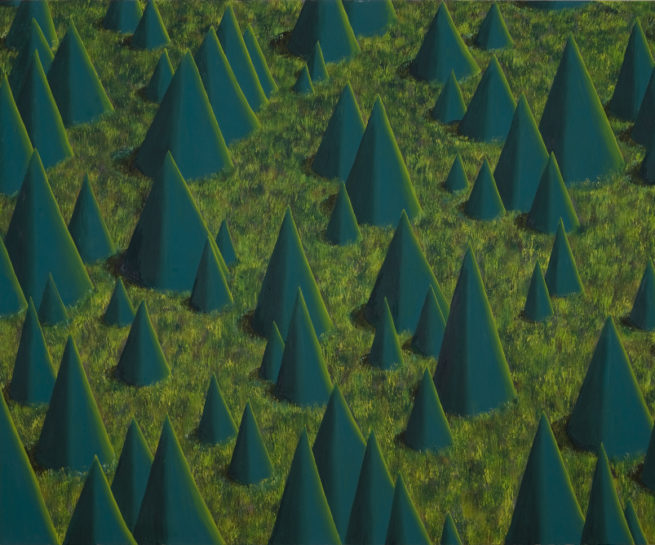

Now, what compelled Roda to conduct his impressive experiment with perspective in “Denkmal für einen Gärtner” (Monument to a Gardener)? A red pedestal, embedded in deep black, serves as a flat surface, stacked upon which we find numerous strips of lush green turf. The cutting edges of these lawn rolls escape the control of real perspective. Fernand Roda: “Perspective fluctuation of the senses and the mind is a prerequisite for perceiving multidimensionality. Within it, the real is quite unreal, and the unreal is real.”

The work was created in 1996 and presented simultaneously with “Strohharfenzyklus” (Straw Harp Cycle) in 2001 in an exhibition, another play with perspective with a pronounced and lasting effect. To this day, the collector that purchased “Sechs nach Theben” (Six to Thebes) is still thrilled when he describes how the rolled lengths of fabric in warm deep red tones evoke the corporeal presence of a real fabric warehouse in the room if one looks at them from a certain distance. Roda: “The depth of the paintings is abstract, not real. There’s no vanishing point. The paintings thus reject their frame and could be continued infinitely in space – a radicality of abstraction.”

Glimpse into the future of fantastical paths, or caricature with a twist

“If someone tells you that something was painted too quickly, you can answer him that he looked too quickly.” – Vincent Van Gogh in a letter to his brother Theo

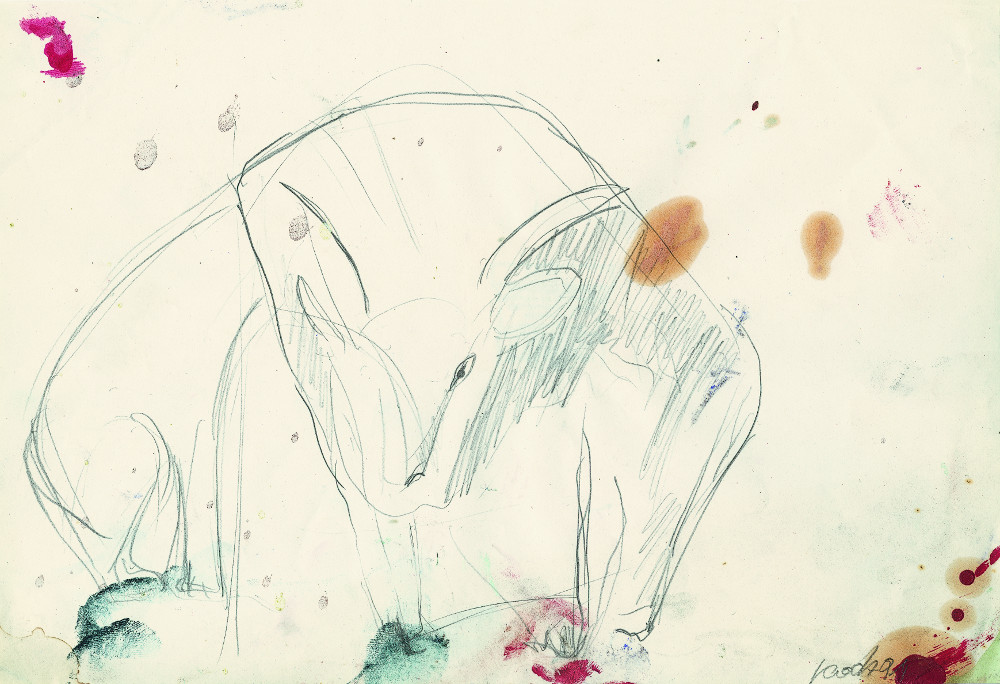

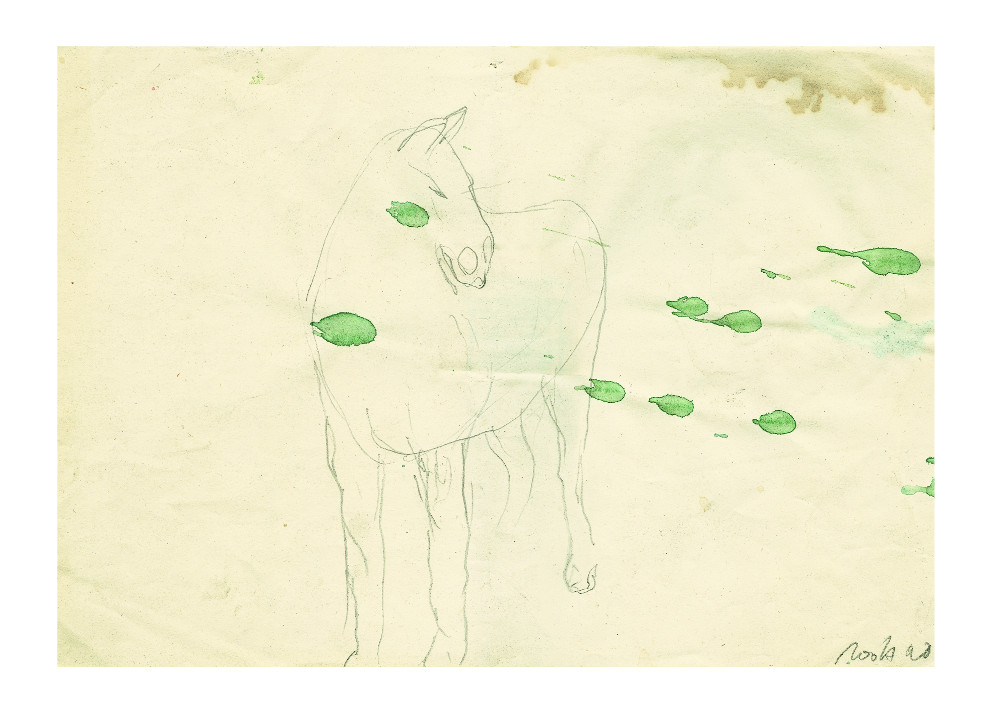

The Olaf Gulbransson Museum is located on the shores of Lake Tegernsee and is dedicated to the memory of the draftsman and caricaturist Olaf Gulbransson (1873-1958). It was founded in 1965 and has been a branch gallery of the Bavarian State Painting Collection since 1973. In this illustrious setting, 300 miniature postcard formats by Fernand Roda will be exhibited next year. The artist has been experimenting with these small compositions since 2000, when he issued the very first New Year’s and Christmas cards for the UNICEF Ethiopia Children’s Fund.

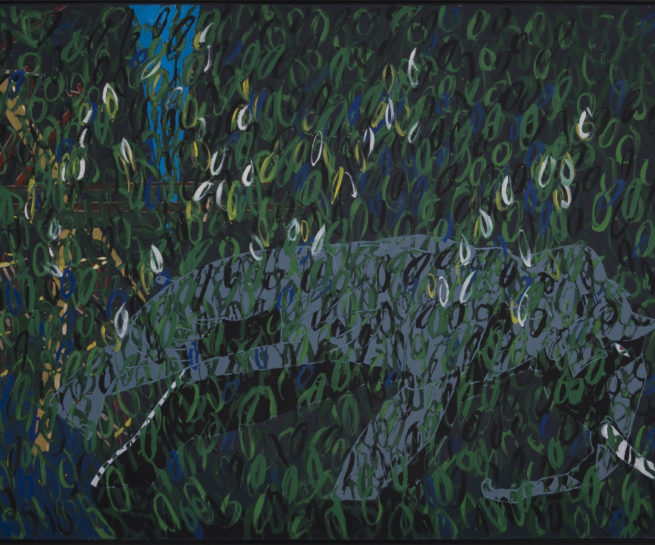

Such miniature works differ fundamentally from the content, method of production and painterly technique of Roda’s usual large-scale formats, and indeed constitute a parallel world. In order to create them, the painter leaves his “day-to-day business” and lets his rich imagination run free. One month each year and with tremendous focus he paints the miniature formats, forming the assembly of a fairytale-like animal world. Contrary to his usually very deliberate painterly modus operandi (densely placed, small brushstrokes that leave nothing to chance), Roda prefers a rather coarse painting style for these small formats, rushing across the canvas in swift movements. Pure painting flourishes in this manner, creating small daring feats that transport the viewer into a wonderful, fantastical animal kingdom with whimsical critters, snakes, birds, reptiles, monkeys or dinosaurs. Besides the chosen subjects, clearly differing from Roda’s large-scale formats, the painting per se is fascinating. It seems as if Roda uses the small formats to let off steam, his spirit is more free, more impulsive, running counter to his usual preference for precise brushstrokes and meticulously constructed paintings.

Dr. Ekkehard Storck – former director of the Deutsche Bank Kirchberg, long-time friend and connoisseur of the painter Fernand Roda, and member of the board of the Olaf Gulbransson Society – will hold the introductory speech at the exhibition opening of “Tierkarikaturen, Fabelwesen aus dem Märchenland” (Animal Caricatures, Mythical Creatures from Fairyland) on July 2, 2006.